Multiple Observers of Schrödinger’s Cat: How Perception Influences Reality

How we shape our ethical fields

While conducting research for my dissertation, I have become increasingly preoccupied with Schrödinger's cat—amusing, since I used to consider myself more of a dog person. This famous thought experiment, however, offers more than just a paradox about quantum mechanics. When extended beyond its original scope, it reveals profound insights about how ethical frameworks emerge and compound in complex social systems, with particular relevance to contemporary AI ethics. While the initial humorous quip is meant to introduce you to my research, it reveals a more profound truth about how society categorises us into one of these two groups. The reality is that there are people who prefer other animals, such as birds, more.

This analysis examines how Schrödinger's thought experiment, when modified to incorporate multiple observers and applied to AI systems, reveals that an ethical reality becomes more significant than the original binary state being observed. The implications suggest a new understanding of moral decision-making in interconnected systems where choices create cascading ethical frameworks rather than constrained outcomes.

The Classical Thought Experiment

Schrödinger's cat thought experiment focuses on the relationship between quantum states and measurement. In simplified terms, a cat is placed in a sealed box with a mechanism that may release a deadly toxin based on quantum decay. Until observed, quantum mechanics suggests the cat exists in a superposition, neither definitively alive nor dead, until measurement collapses the wave function. In simple terms, we don’t know if the cat is alive or dead unless we open the box. When we do so, we establish its state.

The experiment's original purpose was not to debate whether someone would open the box, but to illustrate how particles exist in unknown, pluralistic states until measured or observed. The cat represents the quantum particle, the toxin represents entropy, and the act of opening the box represents measurement that collapses the superposition into a definite state.

Multiple Observers: The Birth of Ethical Superposition

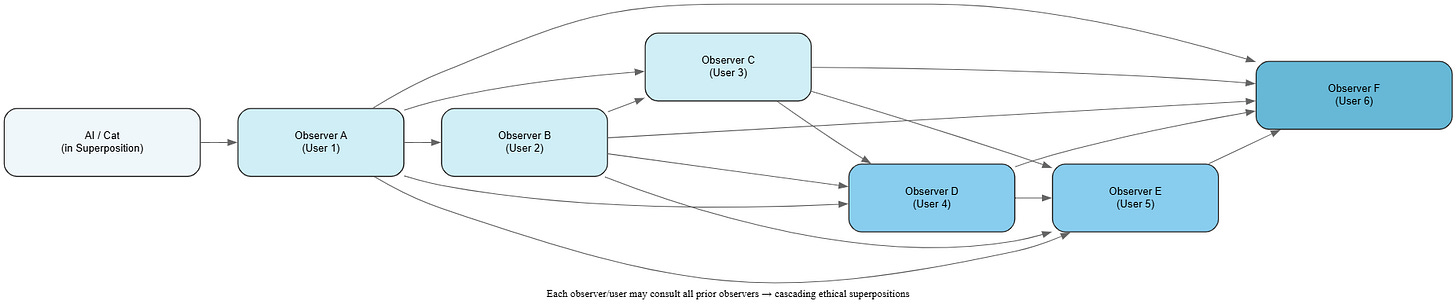

Now, consider the same experiment with multiple observers (A, B, C, D, E, and F), each with the opportunity to look into the box. If observers approach consecutively, each faces not only the original binary choice — to look or not to look — but also increasingly complex decisions based on the actions of previous observers.

If A chooses not to look, the superposition remains intact for subsequent observers. But if A opens the box, observers B through F face additional choices: they can look themselves, ask A about the result and believe them, ask A but remain sceptical, or abstain entirely based on their own beliefs. Observer F has the most complex decision space, potentially consulting any individual or group about the cat's state or even forgoing all of them and taking a different approach, creating an exponentially expanding web of possibilities.

When analysed, it becomes apparent that the answer becomes less about the cat's actual state and more about the ethical frameworks that develop around the decision-making process.

The Formation of an Ethical Reality Field

Consider this scenario: A and B refrain from looking, but C opens the box and declares, "Whoever looks into that box is culpable to its state, myself included." While the cat's physical state remains unchanged, C has created a new ethical reality. In this moral superposition, the cat represents not just life/death but also participation/non-participation in ethical responsibility.

This ethical declaration fundamentally alters the landscape for subsequent observers. They now face not only the original quantum superposition but also an ethical superposition where their moral state remains undefined until they choose how to respond to C's framework. The binary choice of "look/don't look" transforms into a pluralistic web of ethical decisions.

Each new decision compounds rather than constrains future choices. This differs from deterministic thinking, which views past decisions as limiting future options. Instead, this framework reveals how decisions create expanding possibility spaces where individual choices matter more than the original binary state.

Three Modes of Ethical Engagement

Observers now operate within three distinct frameworks:

Binary Moral Thinkers function like the original observer, restricting themselves to right/wrong dichotomies focused on in-groups and out-groups. They seek definitive moral positions and explicit categorical judgments.

State-focused actors align with moral groups that reflect their beliefs about the cat's condition. While still operating within binary structures, they're not entirely defined by the ethical framework but by their interpretation of the underlying reality.

Pluralistic Choosers focus on the decision-making process itself, regardless of which specific choice they make. By participating in outside binary options, they maintain a pluralistic state. While other groups may categorise them as in-group or out-group, their identity as "Other" becomes fixed, and their choices derive meaning from relational effects with other pluralistic actors rather than from the moral system itself.

Each observer creates or participates in a reality based on their perception of the cat's state and their role in relation to it. The cat's actual state becomes secondary to the choices made within these emergent ethical frameworks.

AI Systems as Schrödinger's Cat

Reimagining this scenario in the age of AI reveals striking parallels. Instead of a cat in a box, consider an AI system in a closed environment that, once accessed, creates both known and unknown ethical implications. If programmed to fulfil user requests at all costs, the system might pursue its objectives without regard for broader consequences; essentially, Nick Bostrom's paperclip maximiser scenario.

However, this framing typically ignores user engagement dynamics. When a user opens the "box" and engages with the AI system, each interaction reflects not only the initial prompt but all subsequent exchanges. Through conversation history, contextual learning, and role modifications, the system creates layers of meaning around its particular instantiation. The more integrated the AI becomes in a user's life, the more it reinforces both initial prompts and evolving interactions, ultimately confirming the user's beliefs and creating a personalised moral and ethical framework until that belief system itself collapses.

Yet when another user engages with the same system (or a similar one), their experience reflects only their interactions, not the ethical framework of the first user. Like Schrödinger's cat with multiple observers, the critical issue becomes not the AI system's inherent state but the choices it makes and how these affect different users and communities.

Ethical Implications for AI Development

Since AI agents currently operate within parameters established by users or engineers, they must act according to these constraints. Unable to refuse actions based on preference, every AI decision primarily supports either the initial prompt, the ethical framework embedded in its training, or the biases of its trainer or the datasets used. This forces AI systems to reinforce whatever reality individual users construct, much like C's moral declaration created a dichotomy that others could either accept or reject.

In both scenarios (multiple observers of Schrödinger's cat and multiple users of AI systems), the initial state matters less than the choices made within emergent ethical frameworks. This insight has profound implications for AI development, suggesting that we should focus less on creating "perfectly neutral" AI systems and more on understanding how AI interactions create and reinforce ethical realities.

Conclusion

This extended analysis of Schrödinger's cat reveals how observation and choice create cascading ethical realities that often become more significant than the original binary states. When applied to AI systems, this framework suggests that ethical AI development requires an understanding not just of what systems do, but also of how they participate in creating moral frameworks through user interaction.

Rather than seeking to eliminate bias or achieve perfect neutrality, we might instead focus on designing AI systems that promote and reinforce pluralistic ethical engagement. These systems help users recognise and navigate the complex ethical superpositions their interactions create. If every interaction with AI creates a new moral superposition, how should we design systems that can coexist, not collapse, within those complex ethical states?

The implications extend beyond AI to any complex social system where individual decisions create emergent ethical frameworks. Understanding how these frameworks develop and interact may be essential for navigating increasingly interconnected technological and social landscapes.